Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

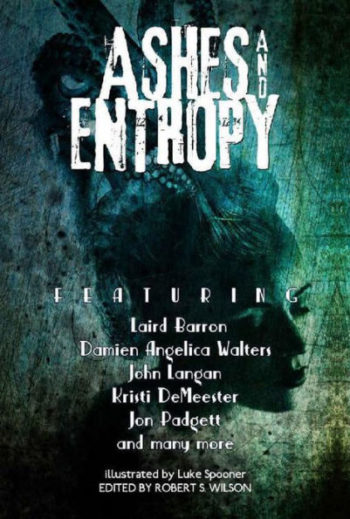

This week, we’re reading Autumn Christian’s “Shadow Machine,” first published in Robert S. Wilson’s 2018 Ashes and Entropy anthology. Spoilers ahead.

“…we were the people who would go further and further into the center, until we were more spiral than the spiral we crawled into.”

Summary

Terra is a “child of the night.” So the doctor said when her infant arm was burned by a mere “slice of hallway light.” Terra suffers from Xeroderma Pigmentosa, a rare genetic disorder that makes her skin too sensitive to bear sunlight or even the ultraviolet radiation of streetlights. So her mother moved them to the country and bricked over their windows. All except the kitchen window, through which Terra begins to see a “midnight man” sporting black velvet hat and briefcase, smoking clove-scented black cigarettes.

He’s there the night mother forbids Terra to attend Moonlight Mass. She heads anyway to the cypress grove into which the moon peers. The grove calls itself the Congregation, and knows her name. She must drink cypress-scented blood from starcups and summon her Shadow Companion to the dance. Only tonight, she’s distracted by memories of the computer her now-deceased father bought her, on which she’s learned to gather images of sunlit valleys. She imagines being someone who hasn’t had seven childhood surgeries to remove melanomas.

The Congregation, angered by her inattention, deserts her. She blames the midnight man and confronts him. He introduces himself as Mr. Leclair, says the Congregation is “small-time.” She should come work with him—he’ll show her better magic.

Buy the Book

Flyaway

Terra takes the microprocessor the midnight man offers, as if it were a talisman. Then she dreams of an unclimbable metal mountain and a metal spider emerging from a metal egg, of golden light filling her internally where it can’t hurt. She accepts Leclair’s offer and goes to the underground Umbra Labs. Four other people marked with Xeroderma’s stigmata tend a machine as hideous and beautiful as her dreams. At certain angles it looks like a “gleaming egg with no unbroken seams,” at others like “a porous insect” poised to strike. It’s somehow bigger than the lab. It sizzles with nightmagic. Terra smells “the moon coating its metal” and hears it whisper: “Terra. Baby. Welcome home.”

Leclair assigns Terra to “fieldwork,” teleporting to other-dimensional planets. She carries a disk programmed and magicked to open a portal back to Earth. All these worlds bathe in light she can tolerate. What possibilities this opens!

Nights, sleepless, she goes to the lab. The machine whispers that it’s been waiting so long for someone like Terra. It was the invisible presence guiding her at the computer and teaching her magic’s language. Now it needs her… to do something for it.

Many nights Terra lies curled beside the machine so they can cradle each other, “armless and voiceless,” while it whispers love stories. During lulls in preparing portal disks, she and her co-workers share stories of pre-lab magical encounters and affirm the machine’s greater magic. It seems to grow bigger and more solid daily, to “[glow] through concrete, pressing its face through solid matter as if it was beyond matter.”

That night Terra goes to the lab and retrieves the newest portal disk. The machine shows her how to reprogram it to go to any planet she wants—any planet the machine wants. Co-worker Melonie’s also there, lying enthralled beside the machine as Terra does. All Leclair’s employees are in love with the machine—why didn’t Terra realize this before?

Melonie opens a panel in the machine. Terra gazes inside, not at circuits but at the world the machine promised her, all mint-colored sky and pillowed valleys and hills crowned with halls where people dance all night. There she’d carry the sun in her pocket and be the source of her own power.

Leclair enters and drags the girls back to their rooms. He warns Terra that the machine isn’t a plaything or her friend. But in her head she hears the machine promising her a place “ancient and beautiful… wrapped in night, kissed by the glow of stars and cool circuitry.”

Leclair locks everything up, but the “children of the night” are clever enough to free themselves. They return to the lab, reconfigure the latest disk and step into the teleport-chamber. The machine whispers that together they’ll create something special and new, all because of Terra’s magic. At the last minute, Leclair tries to stop their interdimensional trip. Failing, he thrusts an arm into the teleport-field. Bad move, for when the five reintegrate on the “other side,” his severed arm lies at their feet.

The five are in a sunless world where “machines cropped from night” rise atop hills like “crooked black teeth.” It’s “stitched from metal dreams… that couldn’t have come into being without a heavy dose of nightmares.”

Terra’s co-workers want to activate the portal-disk and free “whatever horrifying thing” it contains. She flees, intent on throwing the disk into the planet’s darkest corner. On arrival, the machine spoke in a voice “cracked and dirty,” like an “angry sinkhole.” Now its voice grows sweet, telling Terra they’re both “sewn from the dark.” She must build one last thing for it. Or, if she no longer loves it, she must throw away the microprocessor in her pocket.

They reach a colosseum where Terra’s co-workers wait, eyes brilliant red. Instead of tossing the microprocessor, as she wishes she could do, she activates the disk. Her dream-egg spawns a monstrous “spider” which tears down dimensional barriers to dissolve our universe.

Now Terra roams desolate planets, watching the machine restitch reality into “a composite of frantic dreams.” Sometimes she glimpses other children of the night and the shadowmachine. One day it will want them again, and make promises it won’t keep. Still she knows when the shadowmachine needs her, she’ll be “too lonely and too in love” to offer any reply other than:

“Anything you want.”

What’s Cyclopean: Loneliness is a lemon, a membrane that peels off the skin like a sunburn. The word beautiful draws blood from the tip of the tongue.

The Degenerate Dutch: Some rare illnesses give you cancer at an early age. Others… make you vulnerable to helping mind control machines destroy the universe?

Mythos Making: Universe-destroying mind-control machines are pretty good at immanentizing the eschaton. Better than cypress groves and octopus gods, anyway.

Libronomicon: The machines rip history from computers and libraries, wipe the internet clean.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Maybe don’t listen to the dimension-ripping mind-control machines, no matter how lonely you are.

Anne’s Commentary

No wonder Terra’s mother flinches when the doctor calls her a “child of the night.” If Mom’s read Dracula, she’ll remember that’s what the Count calls the wolves that guard his keep. Hold on, Doc, Terra’s no wolf, howling out its dark longings under the moon!

Or is she?

Another character afflicted with XP is Dean Koontz’s Christopher Snow, who first appears in 1998’s Fear Nothing. The second novel in the series is aptly named Seize the Night. Seizing the night is what Christopher—and Terra—must do, since they cannot seize the day. Christopher owns a dog (a black Lab mix), which in the Koontziverse means Christopher’s a Good Guy. Terra has no pet to dispel her loneliness. Mom should’ve gotten her a Lab, or at least a hamster. That might have kept her from falling under the spell of self-serving psychic cypresses and cosmic machine intelligences.

Cosmic intelligences are rarely up to any good. Look at Azathoth. Wait, it’s a mindless blind idiot god, but it has Nyarlathotep to do the thinking for it. I was hoping that Mr. Leclair (ironically, French for “light”) would turn out to be Nyarlathotep, but I hope that about all mysterious guys clad in black and given to cryptic utterances. Instead he appears to be a mere mortal magician, as duped by the Shadowmachine as his employees. It’s the Shadowmachine that shares with Nyarlathotep a sinister goal, namely bringing about the end of the world. Most humans would object to that, or maybe not these days.

Anyhow, here’s Howard on Last Days, out of Fungi from Yuggoth-XXI (“Nyarlathotep”):

Soon from the sea a noxious birth began;

Forgotten lands with weedy spires of gold;

The ground was cleft, and mad auroras rolled

Down on the quaking citadels of man.

Then, crushing what he chanced to mould in play,

The idiot Chaos blew Earth’s dust away.

“Idiot Chaos” would be Azathoth, but it was Nyarlathotep coming out of Egypt with wild beasts licking his hands who set the apocalypse in motion. In the story fragment also called “Nyarlathotep,” Lovecraft describes an ultimate reality much like Christian’s noxious planet where, “on hills like rows of crooked, black teeth, rose machines cropped from night”:

Beyond the worlds vague ghosts of monstrous things; half-seen columns of unsanctified temples that rest on nameless rocks beneath space and reach up to dizzy vacua above the spheres of light and darkness…

In “The Hollow Men,” T. S. Eliot prognosticates that “This is the way the world ends/Not with a bang but a whimper.” Terra’s world ends with “a hissing like black noise ready to boil over,” the song of the Shadowmachine. It’s Terra who whimpers as she wanders through universal wreckage. She’s waiting for another whisper from the Shadowmachine, saying it needs her, it needs her… to do something for it.

Why will Terra obey the whisperer? Why did she obey it in the first place?

Robert Frost writes about the End in “Fire and Ice”:

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

“Desire” is the key word. The desire to be free of her nocturnal loneliness to love and be loved are what drive Terra to make up false Internet identities and cater to the needs of dubious groves and their patron moon. XP has doomed her to isolation; it’s also endowed her with a magical ability beyond her fellow night-children’s. In its turn, the Shadowmachine desires Terra. For whatever reason, it requires a singular magician to switch it on, and Terra is the One.

Supernatural entities bent on universal domination generally recruit mortal allies among the deprived and oppressed, those with little to lose and much to gain. Lovecraft’s go-to cultists were scary non-Caucasian peoples like the Polynesians who introduced Obed Marsh to the Deep Ones, or the mongrel hordes of Red Hook, or the mixed-blooded West Indians and Brava Portuguese who worshiped Cthulhu deep in the bayous of Louisiana. In “Call of Cthulhu,” the “mestizo” Castro tells authorities what the Great Old Ones promise their followers: Once they liberate Cthulhu, they too will be liberated, freed to shout and kill and otherwise revel in joy. Shouting and killing and reveling in joy is what scary non-Caucasians would do, you know, without white people in charge.

Unable to live under their own sun, Terra and her co-workers are deprived of the normal human chance at connection. The Shadowmachine, needing their XP-linked magic, secures them by offering light and love it never intends to deliver. Instead it delivers the opposite: darkness and the deeper isolation of scattered survivors. Tragically, the only love remaining is the illusion the Shadowmachine offers. More tragically, Terra knows she’ll always submit to its insatiable need in exchange for its seductive whispers.

Orwell’s closing line in 1984, “He loved Big Brother,” is heartbreaking. So for me is Christian’s closing line, Terra (the World) murmuring to the Shadowmachine: “Anything you want.”

This is the way the worlds end, again and again.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Some apocalypses are random, or inevitable. They don’t care what you do. Others, though, require some input. Someone to press a button, carry out a ritual, read a book. Those apocalypses are more frightening, because they have to be seductive. Ancient and beautiful and perfect—or at least able to whisper sweet somethings persuasively in the dead of night. They need lovers with much to gain or little to lose.

Because the thing we don’t always talk about, with apocalypses, is that they aren’t the end. Or not only the end. Something grows from the ashes, unpredictable and unrecognizable from what came before. And if this world is hard enough on you, you might be open to those whispers. And if it hasn’t… well, as Lovecraft himself shows all too clearly, it can be pretty uncomfortable to think about those Others getting power to make as much change as they’d like.

Or in this case, to think about powers that might exploit that desperation.

Terra, though, doesn’t fit our world in a way that isn’t entirely the fault of other humans. Xeroderma Pigmentosum is a real, rare illness—though as far as I can tell Christian is somewhat exaggerating the effects. (Less immediate lesions upon sun exposure, more severe sunburn after a few minutes, and a tendency toward childhood melanoma.) Though she’s a computer whiz, she’s convinced she has to hide her nature when she reaches out online. So she never makes human friends, or find an internet support group for others sharing her condition. That seems like a failure on her mother’s part, but given the attention she’s attracted there might also be magic involved. Or maybe Umbra Labs and the various competing apocalyptic organizations have already scooped up all others who’d join such groups. So Terra is stuck yearning for a place to fit in, vulnerable to any social connection. And very used to having not-normal friends.

I do love the competing bad-idea Things, all trying to recruit the Children of the Night. (And only them? Are there other conditions that they find equally tempting?) The Congregation and The Bloodbank and the octopus deity and the shadow machines—half a dozen genres whispering sweet lies, like magical predators lurking around a magical internet chatroom.

The story shifts modes easily depending on which Thing lies closest. The first couple of pages reminded me strongly of Machen: Drink from the starcup, the Moonlight Mass cannot be missed, pay attention to the Deep Dendo or you’ll find that forgiveness is a backwards word. But then we find less “archaic” powers, and machines making portals to other worlds, science fiction that shifts to cosmic horror as we learn the ultimate goal of those portals. Now we’re out of the realm of Machen, closer to Gorman’s “Bring the Moon to Me.” And we learn that the Children are a range of genres themselves. They’re chemists and sorcerers and mad computer geniuses, but it doesn’t matter because all those things aim at the same thing, a world changed enough that all the old stories are lost and the distinctions between genres along with them.

The new universe, and the hard work of making it, don’t offer a place where Terra can be happy. But they offer belonging—the nasty sort that goes along with obedience as “a kind of love.” A cog in a machine, a circuit in a computer—the Children know their place. And they’re connected to their own. And to all the hungry ends of the world, reaching out with sweet lies.

Next week, we return to The Weird, and start an exploration of weird fiction by authors of color, with Octavia Butler’s “Bloodchild.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.